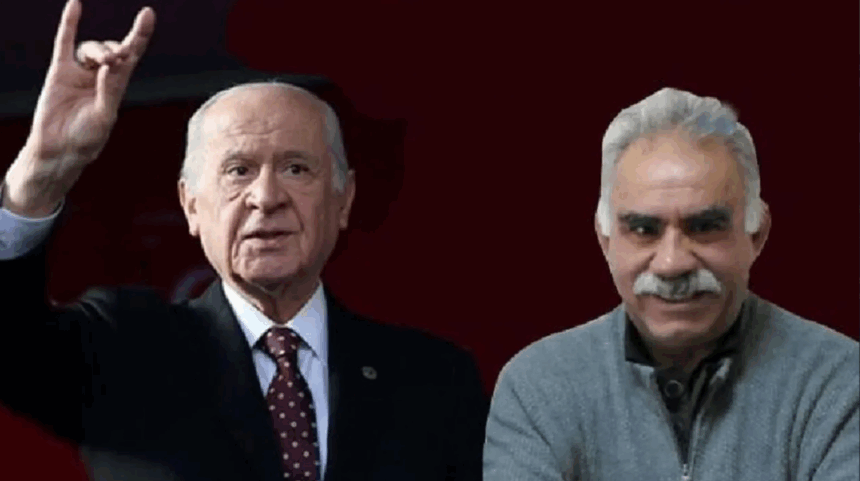

Devlet Bahçeli, the leader of Turkey’s far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and a key ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has said he is prepared to personally visit imprisoned Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) leader Abdullah Öcalan on İmralı Island if a cross-party parliamentary commission decides against doing so.

Bahçeli made the remarks during his party’s weekly group meeting in parliament, arguing that direct contact with Öcalan is necessary for Turkey’s renewed peace initiative with the outlawed group to make any real progress. He told lawmakers that the debate over whether İmralı should be visited had gone on long enough and that, if the commission hesitates, he is willing to go himself accompanied by three MHP colleagues. He first urged the commission to visit İmralı in October and repeated that call on November 4.

Öcalan has been held in an island prison on the Sea of Marmara since his capture in 1999 and is serving a life sentence for leading the PKK, which launched an armed campaign against the Turkish state in 1984. The conflict has claimed more than 40,000 lives over four decades. Turkey, the United States and the European Union list the PKK as a terrorist organisation.

The latest political debate revolves around a new parliamentary body known as the National Solidarity, Brotherhood and Democracy Commission. Formed earlier this year, the commission has been working since August on a legal and political framework to move from armed conflict to democratic dialogue. Its mandate includes proposing reforms to support what Ankara describes as a transition from security-driven solutions to a negotiated political settlement.

Bahçeli told MHP deputies that arguing over the legitimacy of talking to Öcalan was “wasting time” when the country needed concrete steps. He insisted that if Turkey is serious about ending the conflict, “one of the principal actors” cannot be kept outside the process. For that reason, he said, a visit to İmralı is not a marginal detail but a necessary stage in the renewed initiative.

His comments drew a swift reaction from the pro-Kurdish opposition. Tuncer Bakırhan, co-chair of the Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party), said Bahçeli’s statement showed a willingness to assume responsibility at a delicate moment. Bakırhan called on the commission to act quickly, arguing that dialogue and face-to-face meetings are essential to consolidate what his party describes as the second phase of the peace process: a set of legal and political steps following the PKK’s decision in May to renounce its armed campaign.

For DEM, which positions itself as the main political representative of the Kurdish movement in parliament, that second phase requires institutional reforms, the normalisation of Kurdish political life and an end to the criminalisation of elected Kurdish representatives. Bakırhan framed potential meetings with Öcalan as part of this broader shift from military confrontation to civilian politics.

Justice Minister Yılmaz Tunç, commenting on the debate, underlined that any visit to İmralı will depend on a formal decision by the parliamentary commission. By placing the matter in the hands of the new body, the government signals that it wants the initiative to be seen as emerging from an institutional and cross-party process rather than being managed solely from the presidential palace or through back-channel negotiations.

From the nationalist opposition, reactions were more terse. Müsavat Dervişoğlu, leader of the Good Party (İYİ Party), responded to Bahçeli’s proposal with a brief message on X, saying simply, “Let him go.” The remark was widely interpreted as both a refusal to shield Bahçeli from the political consequences of such a move and a way of distancing İYİ Party from any responsibility for talks involving Öcalan.

Bahçeli’s remarks come at a time when his relationship with Erdoğan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) appears under strain, despite the MHP’s central role in keeping the “People’s Alliance” in power since 2018. Over recent months he has made several statements that observers interpret as subtle challenges to the president.

Earlier this month, Bahçeli said that releasing jailed Kurdish politician Selahattin Demirtaş in line with a European Court of Human Rights ruling would be “positive” for the country. The comment stood in stark contrast to Erdoğan’s repeated rejection of that ruling and immediately drew public attention, since Demirtaş remains one of the most prominent symbols of the Kurdish political movement behind bars.

At the same time, recent police operations that have touched figures perceived as close to Bahçeli have fuelled speculation about friction within the ruling bloc. Analysts say these moves suggest Erdoğan is asserting control over discussions about who might lead Turkey in a post-Erdoğan era. According to people familiar with the alliance, Bahçeli is uncomfortable with any scenario in which Erdoğan’s son or another family member would inherit power and wants to have a say in shaping the eventual transition.

The debate over an İmralı visit is therefore unfolding not only as part of a new Kurdish peace effort but also against the backdrop of internal power struggles within Turkey’s right-wing camp. For Bahçeli, volunteering to sit down with Öcalan turns him—paradoxically for an ultra-nationalist—into one of the central figures of the peace initiative. For Erdoğan, allowing or blocking such a visit carries significant symbolic weight in terms of who is perceived to control the process.

Turkey’s last attempt at a peace process began around 2012, when state officials and Kurdish representatives held talks with Öcalan and with the legal pro-Kurdish party at the time, the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Those efforts collapsed in 2015 after the HDP managed to pass the 10 percent electoral threshold and enter parliament with a large bloc of deputies in the June general election, ending the AKP’s single-party majority.

Following that vote, Erdoğan shifted to a more overtly nationalist message. Fighting resumed in the southeast, with large-scale military operations in Kurdish-majority cities, urban clashes and extensive destruction in some districts. The crackdown on Kurdish political figures and activists intensified after the failed coup attempt of July 2016, when the government embarked on a massive purge of state institutions and moved to remove dozens of elected Kurdish mayors and MPs on terrorism-related charges.

Former HDP co-chairs Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ were arrested in this period and remain in prison. Their continued detention is frequently cited by critics and international human rights bodies as evidence that the Turkish state has not yet taken meaningful steps toward a sustainable peace, despite sporadic talk of dialogue.

In that context, Bahçeli’s pledge to go to İmralı if parliament will not is seen by many as both a striking personal move and a test of how far Ankara is actually prepared to go. Supporters of the new initiative say that direct contact with Öcalan is unavoidable if the PKK’s transition away from armed struggle is to be managed without splintering and renewed violence. Skeptics counter that without broader political reforms, guarantees for Kurdish rights and the release of key political prisoners, any visit risks becoming a tactical manoeuvre in Ankara’s internal power games rather than the start of a genuine settlement.