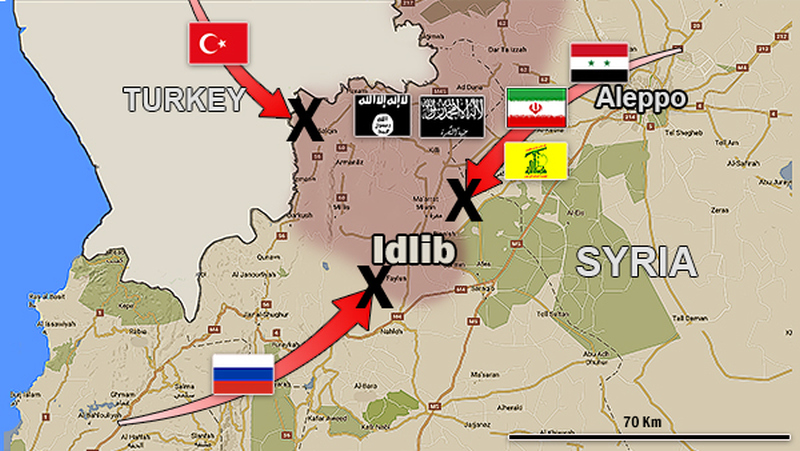

MOSCOW — Syrian air force strikes on a Turkish military convoy in Idlib province Aug. 19 are straining relations between Russia and Turkey.

An Aug. 19 press release on the situation from the Turkish Defense Ministry doesn’t mention Syria once, but refers to the Russian Federation four times — making it clear Ankara sees the deadly incident as a face-off with Moscow.

Turkey said the attack took the lives of three civilians and wounded 12, but provided no information on the victims.

Following Turkey’s statement, Russian officials and state media kept mum, waiting for the Kremlin’s reaction, which didn’t take long. After welcoming French President Emmanuel Macron to Moscow that day, Russian President Vladimir Putin reiterated Moscow’s support for Damascus’ military push in Idlib province.

“I would like to note that before the corresponding agreements were signed in Sochi on the demilitarization of part of the Idlib zone, about 50% of that territory was under terrorist control, and now that number is 90%. We are observing constant raids from there, and more than that, we are seeing the movement of militants from that region to other parts of the world, and this is extremely dangerous,” Putin said.

“There were also numerous attempts to attack our air base in Khmeimim from the Idlib zone, so we support Syrian army efforts to carry out local operations to neutralize these terrorist threats,” he added, signaling Russia’s rationale for the military action in Idlib.

Putin also brushed off Western accusations that Russia violated the very principle of the deescalation zone.

“I would like to remind you that no one ever talked about terrorists having an opportunity to concentrate in the Idlib zone and to feel comfortable operating there. On the contrary, it was stressed that the fight against terrorists would continue,” he said.

Russia and Turkey had seen positive momentum in their relationship, with Moscow acting as a “strategic security provider” to Ankara. Russia delivered the first part of its S-400 missile system to Turkey a few weeks ago, and a number of bilateral projects critical to both parties are underway.

The situation in Idlib, however, has been threatening to sour the relationship for quite some time, with the most dramatic disagreements kicking in since April.

The deal that Russian and Turkish leaders brokered last year in Sochi was expected to navigate the stormy waters, but fell short of serving its purpose. Moscow pins the blame for this failure on Ankara, though it refrains from critical public statements on the subject. Ankara on the one hand supports Syrian opposition groups loyal to Turkey in their battles with the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham coalition of Islamist factions, but on the other hand also carries out military-political moves that ensure Turkey’s strategic presence in this part of Syria.

Russia perhaps could have lived with this if the forces grouped in Idlib that oppose Syrian President Bashar al-Assad presented no security threat to Russian military facilities in Khmeimim. The Syrian leadership, however, can’t be happy with Turkey’s aggression in Idlib and its military presence on Syrian land beyond what was agreed to in Sochi. And while Ankara doesn’t seem to regard Assad as an independent agent in this situation, Moscow has to take the concerns of the Syrian leadership into consideration, if only for the sake of its own reputation as a power loyal to its allies.

In this respect, the continuous shelling and drone attacks on the Russian air base provide Moscow with a perfect reason to back the Syrian army advance on areas that are held to pose a threat to Russia’s own military — something Putin pointed out.

In other words, Assad has a strategic problem with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Idlib, while Putin has a tactical one. This doesn’t necessarily make things any easier for any party, but provides a reason to believe that Russia and Turkey are unlikely to go to war with one another over Idlib — if, of course, no major incident happens to change their positions toward each other.

Another reason to presume the parties are capable of playing it cool is the communication issue. Among the many things Moscow and Ankara learned during the stress test of November 2015, when Turkey downed a Russian jet, was the need to communicate with each other, rather than past each other, when deadly incidents occur. As there have been only a couple of public statements on the attacked convoy so far, some military-to-military talks may be underway that seek a “professional” resolution rather than an overload of public emotions.

However, as the fighting in the Idlib “deescalation” zone rages on, pretty much all the options on the table are uncomfortable for both Russia and Turkey. To make matters worse, pro-regime forces continued their advance Aug. 20, surrounding Khan Sheikhoun in Idlib after the rebels withdrew. That action is critical as the rebels now control no part of the M5 highway, which was their main supply route in and around Idlib.

This leaves Ankara to choose whatever it considers the lesser of two evils.

One option may include additional Turkish reinforcements and subsequent escalations with the Syrian army and, by extension, Russia — something that seems to be happening just now. Another option may imply an updated, if not a new, deal between Ankara and Moscow that — even though it might not sit well with Erdogan and his constituency — might still be better than open hostilities with Putin.

Russia, in turn, also risks getting itself dragged into a conflict that has little to do with the overarching objectives of its Syria campaign, which were mostly about dealing — both constructively and destructively — with the United States, not the local powers. In theory, Russia could agree to the Ankara-backed Syrian opposition groups’ control of the Idlib area, providing Turkey guarantees unhindered traffic along the M5 highway, as stipulated by the Sochi memorandum. Ankara, too, could agree to this solution provided no combat activity affects Turkish observers’ posts on the front line. The problem here, however, may be the way in which the Syrian army redraws the borders of the deescalation zone.

A popular Russian joke suggests that “a marriage of convenience” may prove the best solution, as long as the “convenience” is rightly calculated. In Idlib, Moscow and Ankara seem to be trying to ensure the “marriage” has common strategic interests.

By Maxim A. Suckhov

Source: Al – Monitor