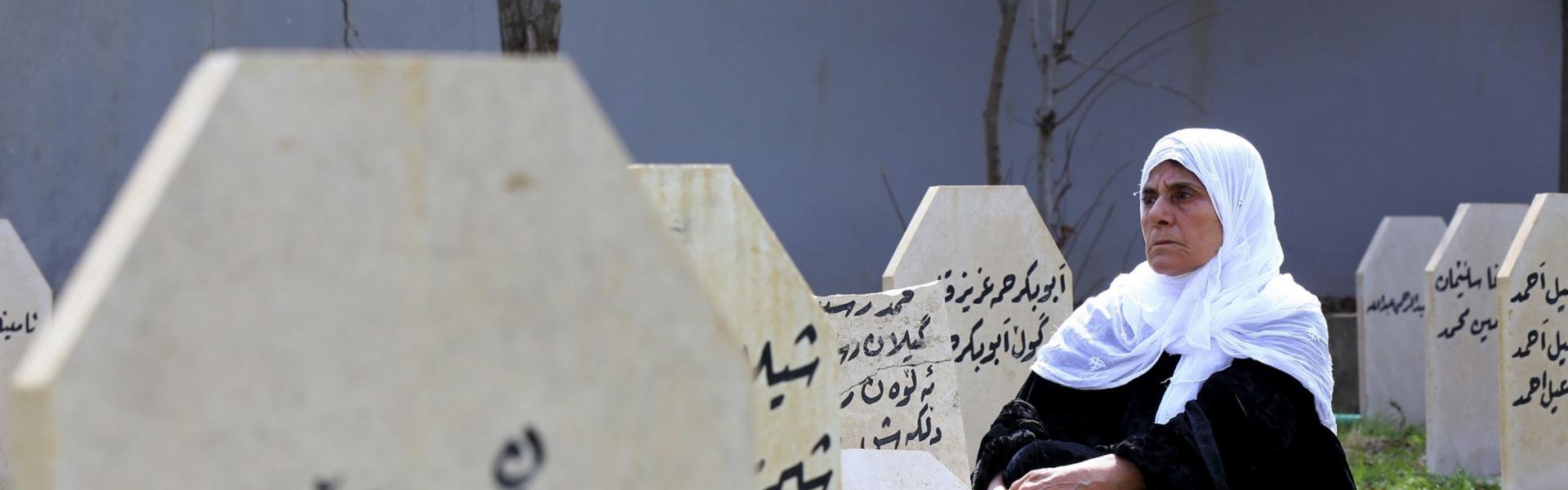

Saddam chose the name “Anfal” for a genocidal attack on Iraqi Kurds that he launched in 1986 and continued until 1989. The name for this massacre, which reached its peak in 1988, was taken from a Quranic verse. In this campaign, which was led by Saddam’s nephew Ali Hassan al-Majid, an estimated 180,000 men and women of all ages were killed.

These massacres, perpetrated with chemical weapons, represent a dark chapter in history and have been officially recognised as genocide by Sweden, Norway, South Korea, and the United Kingdom. Recently, Iraqi Kurdish news outlet Rudaw published an article about Anfal written by David Romano, a professor of Middle East politics at Missouri State University.

In this article, which provides important insights about Turkey’s Kurdish policy, Romano recounts his travels in 2003 from Canada to Iraq to organise an extensive humanitarian effort. He was surprised by the hatred Christians in Baghdad expressed towards Kurds:

“At first I wondered if I was speaking to a group of Tariq Aziz hopefuls. Tariq Aziz, of course, was Saddam’s Iraqi Christian Foreign Minister and a loyal Ba’athist until the bitter end. But then it occurred to me that these people were simply from Baghdad, born and raised in the propaganda capital of a regime that dehumanised and demonised the Kurds for decades. Despite their own identity as an Iraqi minority that often had to grapple with xenophobia and intolerance, many of them identified with and believed in a narrative that justified the worst imaginable crimes against the Kurds.

As Kurds in Iraq commemorate the Anfal this week, it may thus prove useful to reflect on some of the pre-conditions for genocide. One of the first preconditions is that the target victim group be excluded from the rest of society. In Saddam’s case, this involved branding the Kurds as rebels, Iranian agents and even “infidels.” In this vein, Saddam famously asked Muslim scholars in Iraq to issue fatwas against the Kurds branding them as non-believers – a request that many Sunni Imams obliged, while Shiite imams by and large refused to do so. Some of the Baghdadi Christians hosting me in 2003 also apparently accepted this narrative, not realising how dangerous such a precedent would be for them later when others decided to brand Iraqi Christians as enemies as well.

Another precondition for genocide rests on the presence of a dictatorial state. When no checks on the power of the ruling elite exist and where rule of law simply depends on the whims of the dictators, humanity’s worst impulses and nightmares become possible. Iraq under Saddam was such a state, of course, to the point that even Kurdish tribes recruited to help carry out the Anfal against their kin could not refuse for fear that their villages would be next if they did.

A third precondition revolves around the existence of a crisis or opportunity that makes genocide possible. The Iran-Iraq war, especially as the tide turned against Baghdad in the latter years of the conflict, provided just such a crisis. When Kurdish parties in Iraq cooperated with Iranian forces against their long-time enemy in Baghdad, Saddam’s wrath did not differentiate between Peshmerga and Kurdish civilians…

A fourth and final precondition for genocide merits the most attention, however. For genocides to really unfold on a large scale, bystanders – other members of society in places like Baghdad and abroad, as well as other states – need to do nothing. The Kurds remember this all too well: Few in the international community said a word as the Anfal unfolded. Saddam used European and American-supplied weapons and chemicals to eliminate whole swathes of Iraqi Kurdistan, but the Kurds could not even get a hearing in the United Nations about it. Saddam remained an ally of Europe and Washington because he was useful against Iran… Only when Saddam invaded Kuwait in 1990 were the reports of Halabja and other Anfal atrocities retrieved from the filing boxes and shelves where they had lain for the past two years.”

Unfortunately, Kurdish people in Turkey are faced with a similar exclusion and demonisation. Some may recall a public speech of the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s from 2015 that exemplifies such attitude:

“Haven’t these people burned down and destroyed our mosques? These people are atheists, they are Zoroastrians [referencing an ancient Persian religion]. They will amount to nothing. They do not act in accordance with our values, nor will they. I believe that sooner or later, my brothers in Diyarbakır [a major province in Turkey’s southeast] will teach them a lesson at the ballot boxes. We follow the ballot boxes. These people follow Qandil [the headquarters of the outlawed PKK]. We take our power from God and the people. That is what makes us different.”

In recent local polls on March 31, Erdoğan continued to exhibit the same attitude by equating Kurdish people and their political representatives in the Peoples’ Democracy Party (HDP) with terrorists. Just like Baghdad’s Christians, people living in Ankara, Izmir, and Istanbul are being shaped by Erdoğan and the state’s propaganda machine, and have internalised this rhetoric about Kurdish people.

While the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) declared victory in several major provinces in March 31 elections thanks to support of the Kurdish voters, it has been careful to avoid any association with the HDP and has refrained from criticising the decisions of the Supreme Election Council, which in effect means stealing the municipalities from the HDP in eastern Turkey. Kurdish people find themselves isolated and ostracised.

It is impossible to defend the idea that Turkey is still a democracy. Currently, the country is governed by an executive and judicial system built on Erdoğan’s whims and preferences. Turkey is under a dictatorial regime.

An existential crisis is impending. The crisis that Turkish-American relations will likely undergo, catalysed by Turkey’s purchase of Russian S-400 missiles, will destroy an already precarious Turkish economy. Turkey could attempt to conceal such crises with a military adventure in Syria against Kurdish militia or finding other external enemies.

Kurdish people in Turkey are living under pressure and oppression, with a large audience both domestically and internationally. With the CHP at the forefront, many actors are simply watching by from the sidelines. The European Court of Human Rights is performing all sorts of acrobatics to avoid taking up the Kurdish issue. Since Europe is not in a position to withstand a wave of migration from Turkey, it will continue looking the other way as rights violations occur.

Unfortunately prospects for Turkey do not look good. We should recognise that if we cannot come together to support true democracy and the rule of law, if we submit to Erdoğan’s rhetoric, we will find our country in ruins.

By Ergun Babahan

Source: Ahval News