ISTANBUL — In the weeks since Turkey’s government accelerated a crackdown on Syrian refugees, arresting thousands of people and deporting untold numbers back to Syria, the refugees and their advocates have warned that the policy could be fatal as the migrants were returned to a war zone.

For one Syrian family, those fears were realized this week. Hisham al-Mohammed, a 21-year-old Syrian refugee who was deported to Syria’s Idlib province in June, was shot and killed Sunday while trying to illegally cross the Turkish border to get back to his family in Istanbul, his father said.

Hisham was in Syrian territory when he was killed, his father, Mustafa al-Mohammed, said in an interview Friday morning. Hisham had been walking with a group of Syrian refugees and was shot after he stopped to pray a few hundred yards from the Turkish border wall, according to his father, who said he had spoken to a friend and a relative traveling with Hisham.

The shots came from the direction of the wall, which is patrolled by Turkish troops, they added.

Hisham’s arrest, deportation and killing raise troubling questions about Turkey’s evolving policy toward the more than 3.6 million Syrian refugees the country hosts. Turkey has been considered a haven for refugees throughout Syria’s civil war, with the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan providing visitors with access to services such as education and medical care, official identity papers and a measure of protection.

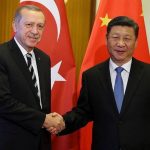

Mustafa al-Mohammed, left, said his son, Hisham, was shot and killed near the Turkish border after he was deported from Turkey in June. Hisham’s brother Tayseer is shown playing with two of Hisham’s young children. (Kareem Fahim/The Washington Post)

But public impatience with the growing number of refugees has appeared to shift the government’s stance. Turkish officials speak frequently now about returning hundreds of thousands of Syrians to areas of their country that the Turkish military controls and deems secure.

“We aim to accelerate the return of emigrants, who have been homesick for eight years, to their country,” Erdogan said Tuesday in Ankara. A Turkish agreement with the United States to establish a “safe zone” in northern Syria, announced Wednesday, explicitly mentioned the return of displaced Syrians as a reason for establishing such a zone.

The arrests, mostly in Istanbul, have spurred many Syrian refugees to go into hiding. Turkish officials have said the roundups are aimed at returning Syrians to Turkish cities where they are permitted to reside — a measure designed to ensure that no city or town is overwhelmed. Officials have also denied carrying out involuntary deportations.

But Hisham’s arrest and deportation appeared to violate the government’s own rules. After moving with his family to Turkey from near the Syrian city of Aleppo three years ago, he obtained an identity permit that allowed him to live in Istanbul — Turkey’s largest city, and a coveted destination for refugees because of the relative abundance of work. Hisham found a job as a tailor, and he was the only member of his family with steady employment, his father said.

He showed a reporter a copy of Hisham’s Istanbul identity document and said other members of the family also possessed similar documents. “I followed the rules,” the father said.

But for reasons that remain unclear, Turkish security officers raided the family’s apartment late one night in May, the father said. They separated the men and women, searched the apartment and took pictures of the family’s identity papers, he said. There had been no run-ins with neighbors or employers that would make them obvious targets of such a raid, which was carried out by uniformed and plainclothes officers wearing bullet-resistant vests and carrying heavy metal shields, he added.

When the search was done, they said Hisham had to come with them.

“My son looked at me. I said, ‘We are in Turkey and we follow the rules. Put your clothes on.’ ” Hisham left with the officers, his father said.

Turkey’s interior ministry did not immediately respond to a message seeking comment about Hisham’s arrest and deportation, or the allegation that he had been shot by Turkish personnel.

He was held for several weeks at a police station, then moved to a detention center for migrants, the father said. His son was treated well while in custody and was allowed regular visits from his family. The guards at both facilities were friendly, but like the family, they seemed to have no idea why Hisham was being detained, Hisham’s father said.

The family hired a lawyer at one point, but they were not able to get Hisham released. He was never brought before a judge, his father said.

Then, on June 19, Hisham’s father received a call from another Syrian detainee saying his son was being sent back to Syria. The next call he got was from his son, who said Turkish authorities had dropped him at the Bab al-Hawa border crossing between Turkey and Syria. The father was panicked, but Hisham sounded relaxed and sent a smiling picture from the crossing.

Along with his extended family, Hisham had left his wife and three young children in Turkey: The youngest, Shuaib, was born the day before the police raid. Hisham’s father approached the Red Crescent for help but was told they could not bring his son back from Syria. Hisham tried to cross the border two or three times, his father said, before his attempt Sunday.

A bullet entered Hisham’s ear and exited his back, according to his father, who was sent a picture of his son’s body and an autopsy report. The shooting did not stop after Hisham was killed. Other refugees had to crawl to retrieve the body, his father said.

For several years, human rights groups have condemned Turkey’s use of forceto deter refugees trying to cross the increasingly perilous border.

“I lost my son, and we lost the one who supported us,” Hisham’s father said. “I lost my son. I wish this shooting at people would stop.”

Source: Washington Post