Ethnic cleansing of Uighurs in China has forced an exodus to Istanbul—and a desperate effort to keep their culture alive.

ISTANBUL—On a Sunday morning in April, 9-year-old Nefise Kerim dragged her older sister, Saniya, to a bookstore in Istanbul’s Zeytinburnu neighborhood. The girl’s brown eyes scoured the bookshelves full of colorful tomes depicting an Arabic script.

Kerim wanted to come after she had seen an announcement on Facebook that a new magazine for Uighur children was out. The publication, called Four-Leaf Clover, is the first literary magazine abroad written by Uighur children for Uighur children. Its editor, Uighur-language teacher and poet Muyesser Abdulehed, wanted to give children from her ethnicity a chance to see a reflection of themselves in public and to show them that their community has a voice in its mother tongue.

Kerim’s eyes grew with excitement as she held her copy of the magazine. On its cover was a drawing of an angry plump man holding a bag of presents—the Uighur tradition’s answer to Santa Claus. Copies of the magazine have made it into the hands of Uighur children living in a dozen countries, but not to their homeland, the Chinese region of Xinjiang, where the government has outlawed their language in schools and is on a mission to erase their culture.

The Uighur teacher and poet Muyesser Abdulehed holds a copy of Four-Leaf Clover, the first literary magazine abroad written by Uighur children for Uighur children, on April 21.

In the past few years, more and more Uighurs, a minority who speak a Turkic language and call Xinjiang home, have moved to Turkey as they flee an assimilation campaign led by Beijing. Some live in Zeytinburnu, a neighborhood adjoining the sea that for decades has been a safe haven for immigrants from the Middle East and Central Asia. Traveling to Turkey has been possible for Uighurs, who are seen as culturally close to Turkish people. But once settled there, many live in a legal limbo, without resident or work permits or the possibility to renew their Chinese passports.

Experts estimate the Chinese government has placed up to 1.5 million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in political indoctrination camps in the past few years. Many of their children have been placed in what the government calls “boarding schools,” where they are taught Mandarin Chinese and “good life habits.” Beijing says its campaign is needed to root out terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism. But the seemingly arbitrary detentions, mass surveillance, and clampdown on religious expression suggest an aim to instill fear and strip Uighurs of their cultural and religious identity. “[China’s] treatment of the Uighurs should be called what it is: cultural genocide,” wrote James Leibold, an associate professor of politics and Asian studies at La Trobe University.

In Zeytinburnu, Uighurs have rebuilt some of what has been erased from Xinjiang. Uighur restaurants serve slippery noodles in rooms adorned with symbols of their ancient culture, such as wall carpets depicting the now silent Id Kah Mosque or a famous painting of a Uighur musical ensemble. Women wearing headscarves shop at fragrant fruit and vegetable stands wrapped around street corners, while children play football in the cobblestone streets.

A Uighur family attends the National Sovereignty and Children’s Day party in the Uighur neighborhood of Sefakoy in Istanbul on April 23.

Despite the neighborhood’s liveliness, the community’s open secret is that everybody has somebody inside the camps. The answer by some community members to China’s crackdown has been to create a de facto cultural resistance. Through music, painting, poetry, education and fashion, Uighurs in Istanbul are working to maintain the richness of their identity and convey a more powerful message to the world.

“We cried for more than two years, and we protested for more than two years, but nothing changed,” said Yusuf Sulaiman, a musician who at the end of last year formed an already popular Uighur band in Istanbul. “So I thought, we must change our style, we must do something, find another way.”

For some, the pivot was prompted by the responsibility to create an emotionally healthier environment for Uighur children—and to prepare them for a longer campaign of cultural resistance. Abdulehed, who holds Uighur-language classes on Sundays, said that Uighur children carry a lot of pain and anger, which she tries to channel into their studying hard. “For example, they’ll tell me they want to be a soldier,” Abdulehed said. “I’ll tell them, ‘OK, being a soldier is a good thing, but being an illiterate soldier is not a good thing because illiterate soldiers always lose in fights. So let’s be strong, let’s be knowledgeable.’”

Abduhelil Haji works in the Sutuk Bugrahan Bookstore in the Zeytinburnu neighborhood of Istanbul on April 21.

The extent of the damage inflicted upon Uighur culture is difficult to convey. Over the past few years, Beijing has imprisoned more than 300 Uighur cultural elites, including poets, novelists, anthropologists, university professors, and scientists.

The imprisoned authors displayed in Uighur bookstores in Istanbul are the culture’s literary giants. There are the books of Halide Isra’il, a beloved sci-fi novelist who was detained at 75. There are the works of Mirzahit Kerim, who was arrested as a young poet in the 1950s for writing about a baby in a box, which the Chinese government saw as a separatist metaphor. He was released in the 1980s, continued to write novels and was re-arrested recently, at the age of 82. There are the books of pioneering anthropologist Rahile Dawut, once a celebrated professor at Xinjiang University who disappeared in late 2017. The university’s former president, Tashpolat Teyip, who also vanished in 2017, was the subject of an “urgent action” appeal this month by Amnesty International, which says Teyip’s family fears his execution.

“They’re decapitating the entire culture,” said James Millward, a professor of history at Georgetown University, who considers the Chinese government’s techniques reminiscent of those used during the Stalinist terror of the 1930s.

For Uighur artists in Istanbul, the crackdown in Xinjiang feels both all-encompassing and personal. Ilminur Mutelip, a 22-year-old painter, poet, and calligrapher, lost contact with her parents a year after she moved to Ankara to study theology at university, in 2016. She started having nightmares of her parents being tortured, and during the day she would feel “mentally deranged,” she said. With little in terms of coping mechanisms, she turned toward her childhood passion for painting, as well as poetry and calligraphy, which was her father’s profession.

“I didn’t communicate with anyone about my feelings, thoughts, and attitude toward life because I felt like whatever I would say to them, they wouldn’t be able to understand or sympathize,” she said. “I released all these thoughts and feelings onto the page through my writing.”

A mosque popular with many Uighurs in Istanbul is seen in the Zeytinburnu neighborhood in April.

Mutelip likes to paint the high desert around her Xinjiang hometown of Kumul and the faces of old Uighur people. In the past few years, she has become involved in artistic projects such as drawing the covers of Uighur children’s books and the plump man on the first issue of Four-Leaf Clover. She is a staunch advocate for teaching the Uighur language to new generations and wants to launch a calligraphy class. Uighurs in the diaspora understand it is up to them to care for their culture. They know that those inside Xinjiang can no longer study their mother tongue and Uighur literature in school; they cannot go to the mosque with their families; they cannot take pride in being Uighur; they cannot spend leisure time with their families without worrying about family members who are in detention.

Abduljelil Turan, owner of the Taklamakan Uygur Neshriyat bookstore and publishing house in Zeytinburnu, hopes one of the exiled authors will write a masterpiece about the Uighurs’ current condition. As he waits, the 61-year old has taken it upon himself to collect the biographies of the detained Uighur cultural elites. “We need to tell the world we exist,” he said. Turan works tirelessly to keep his business and heritage going, but he calls himself a realist. He believes that the fear and pain experienced by Uighurs abroad, combined with the pull of their host countries’ cultures for younger generations, will lead to the gradual disappearance of the Uighur language over the next decades.

“Some people say that we can protect our language until the end of the world,” he said. “But that’s just not realistic.”

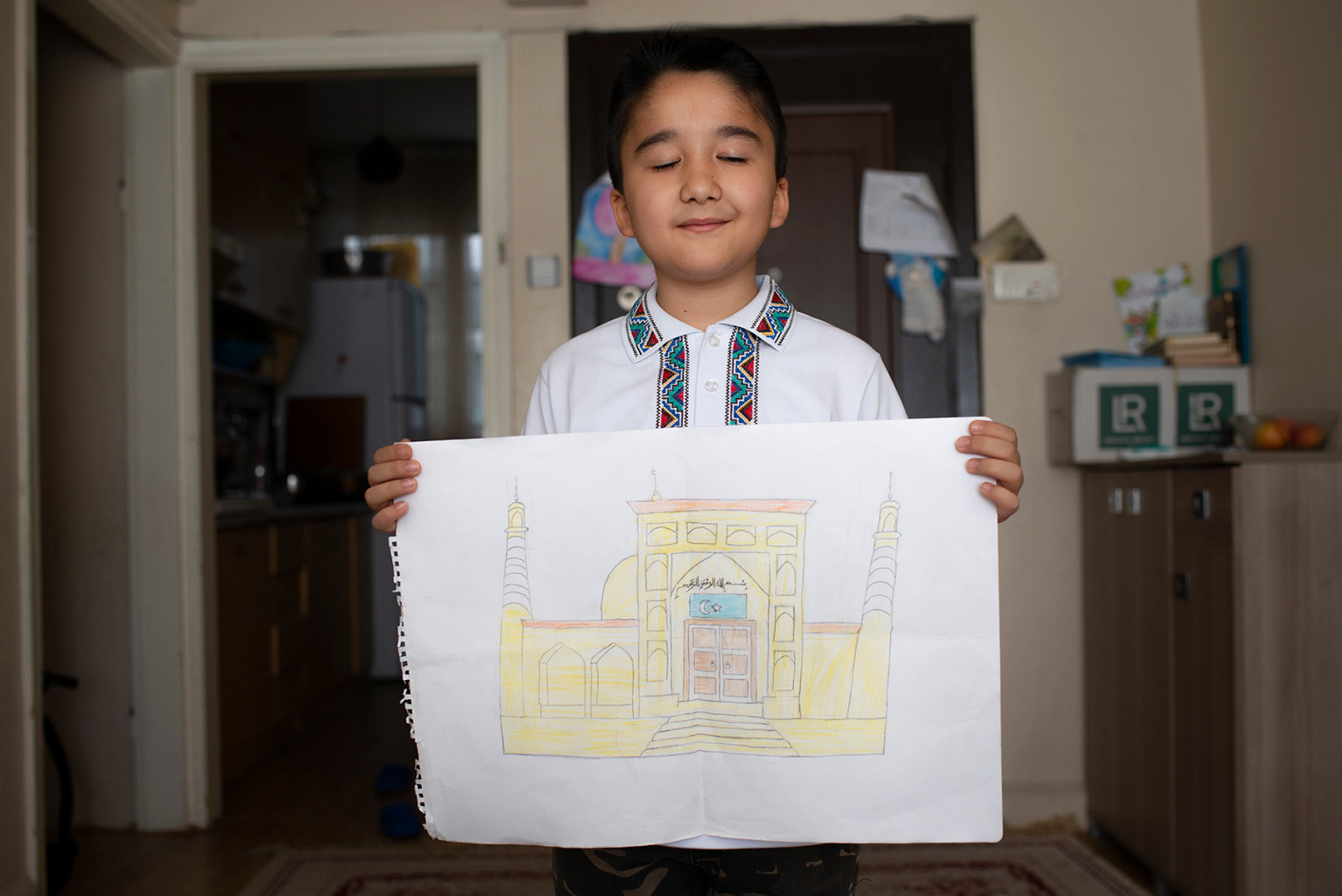

At his home in Istanbul’s Fatih neighborhood, businessman Habibulla Muhemmet has enacted a rule that everybody must speak Uighur at all times. His four children, ages 3 to 10, seemed to comply happily on a Saturday in April as they were running around after a breakfast of beef and rice, carrots, cucumber salad, and homemade bread. The older boys took turns reading from a Uighur children’s book to Muhemmet and his wife, Mihriban Abduweli.

The family moved from Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, in March 2017. A friend of Muhemmet’s in the police warned him to leave the country no later than the end of the month. Muhemmet was at the time running an import-export business with Turkey after the Xinjiang government closed down his two stores and a factory that was making traditional Uighur clothes and activewear. The forced shutdowns were painful for Muhemmet, who had started out in business at age 12 by selling socks on the streets of Urumqi.

Habibulla Muhemmet and Mihriban Abduweli have breakfast with their family in the living room of their small apartment in the Faith neighborhood of Istanbul on April 27.

Muhemmet moved his wife and children to Istanbul, but left behind his older sister. For a while they communicated by sending flower emojis through the messaging app WeChat to signify that they were safe. But in September 2018, he stopped hearing from her. He later learned his sister had been detained. He doesn’t know what has become of his brother-in-law and two nieces.

Muhemmet now runs a small store in Fatih that sells almost exclusively Uighur products, though he admits he would probably make more money if he served the general Turkish public as well. Besides selling traditional Uighur hats, scarves, costumes, and musical instruments, he designs modern clothes with traditional Uighur patterns that he hopes people will wear for any occasion.

But for every Abdulehed, Mutelip, and Muhemmet who pours their pain into their work, there are possibly many other Uighurs who are too scared to express themselves publicly. Sulaiman, the musician who launched the band at the end of last year, moved to Istanbul in 2016 after he was denied visas to the United States and the European Union. He said he doesn’t feel safe in the city, as Turkey could at any time decide to deport Uighurs back to China. He is also afraid of Chinese spies, to the point where he can hardly sleep at night and only takes naps during the day.

The existence of Chinese spies in Uighur communities abroad is well documented. Often, Uighurs become spies for Xinjiang police under threat that if they don’t cooperate, their family members back home will suffer. During our days reporting in Istanbul, we often felt watched, both in the streets and at our hotel. At one point, while we were conducting an interview in a Uighur restaurant, a Uighur man sat at a table next to us and stared at us, scowling, until we left.

Muhemmet said he sometimes feels overwhelmed by pain and anger, to the point where he has thought of “doing something,” but he doesn’t want to harm the image of his community. Instead, he turns to his work. “I think it is my responsibility to do things I’m good at to protect my culture,” he said. “Otherwise, what can I tell my children in the future? What can I teach them? What can I leave them?”

The Turkish flag is seen through the apartment window of Yusuf Sulaiman, a Uighur musician who now lives in Istanbul, on April 24.

Inside Xinjiang, most Uighur parents don’t have the luxury of asking themselves such questions. On a packed bus in the oasis town of Kashgar in November, a young woman was holding a colorful bundle in her arms. At a closer look, I could see it was a baby, almost fully covered and sleeping despite the commotion around it. The bus stopped at a checkpoint between the city and an adjoining county. All the Uighurs, including the mother and her baby, were ordered off the bus. They had to go through a security screening, passing through facial-recognition scanners that matched them with their IDs. Meanwhile, the Han Chinese travelers waited on the bus.

It’s fair to wonder whether that woman is still free, whether she can still care for her baby, or what language the child will speak and what identity he or she will have as an adult.

The architect of the current campaign, which includes ubiquitous surveillance, the internment camps and methodical family separations, is widely seen as being Chen Quanguo, the Xinjiang party chief, who was transferred in 2016 from his previous posting in Tibet.

The government’s grip on Xinjiang had started to tighten ever since ethnic riots in Urumqi left hundreds dead in 2009, followed by terrorist attacks by Uighurs in Beijing and the southern metropolis of Kunming. In March 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping called for erecting a “great wall of steel” around Xinjiang to contain the violence.

Concurrently, an ideological shift regarding the treatment of minorities was happening at the highest levels of the Communist Party, according to Millward, the Georgetown University professor. Since the early 1990s, China had regarded its 55 officially recognized minorities as the building blocks of national identity. But starting around 2014, this has shifted toward the Chinese civilization being seen as the root of all other ethnic groups—a view shared by the country’s nationalist leaders in the 1930s.

“On the policy level, I think that underpins this much more assertive and directly assimilationist approach,” Millward said.

Beijing sees the assimilation of minorities such as Tibetans and Uighurs as necessary in order to secure the country and its borders, said Rachel Harris, a researcher focused on Uighur culture at SOAS University of London. This radical approach fits into the context of Xi’s across-the-board crackdown on civil liberties.

Experts say the clampdown aims to bulldoze over the Uighur culture by targeting the three pillars of language, family structure, and religion through the ban on Uighur language in some schools, the mass detainments, and the demolishing of mosques and ancient rite sites.

At the same time, the government likes to parade Uighur culture by staging events for visitors. Thus Uighurs are asked to perform in public acts for which they would be punished had they done them in private. For example, in a deeply ironic image, Uighur men wearing fake beards performed in a play in front of Kashgar’s old town in November. Growing a beard is illegal in Xinjiang because it is seen as a sign of religious extremism.

“What we’re seeing inside Xinjiang is the hollowing out of Uighur culture, so we’re left with this shell, this outward presentation, but the heart of it is gone,” Harris said. It is left to Uighur communities in the diaspora to preserve, express, and develop their culture.

Left: Muhemmet poses in his small textile store in the Fatih neighborhood on April 21. He almost exclusively sells Uighur products. Middle: The East Turkestan separatist flag, used by Uighurs abroad as a symbol of their independence, hangs on Abduweli and Muhemmet’s bedroom door in their Istanbul home on April 27. Right: Sulaiman of Dolan, a popular Uighur band in Istanbul, poses inside his apartment in Istanbul on April 24. “We cried for more than two years, and we protested for more than two years, but nothing changed,” Sulaiman said. “So I thought, we must change our style, we must do something, find another way.”

In the face of Beijing’s assimilation campaign, some Uighurs in Turkey already find hope in efforts to maintain their cultural heritage. Uighur culture is resilient because music, religion, and poetry are intertwined and part of people’s everyday lives, said Ferhat Kurban Tanridagli, a linguist and award-winning musician in Istanbul. He gave the example of meshrep—a traditional gathering involving music, dance, poetry, and conversation held at major moments in people’s lives, such as births, weddings, and circumcisions. Many young Uighur children are taught poems by their parents in a way similar to Western families reading to children before bed. Many learn from their parents to play the dutar, a traditional musical instrument with two strings. The dutar’s low tones lend it to being played at home, in the evenings, without disturbing the neighbors.

Tanridagli wants to establish a Uighur Twelve Muqam musical ensemble in Istanbul, named after a centuries-old 12-part music series that is usually played over several days at music festivals. He also wants to open a Uighur museum in Turkey. Although he says he will keep working for as long as he has the energy to do so, he is not overly optimistic about what a small group of dedicated individuals can accomplish.

“The Uighur culture is in danger,” he said. “If the Chinese communist system will continue for a long time, it really will be a problem. But we can’t solve this problem by ourselves, and every human being has to take action and speak up for justice.”

Several Uighurs in Istanbul echoed a sense of powerlessness from feeling like they have been abandoned by the world. Muhemmet, the businessman, said: “If you lost your cat or your dog, it would be your responsibility to find it. And we are members of this world community. Why do we not belong to this family?”

Many in the Uighur cultural resistance believe that once whatever they are making reaches international prominence—whether they are educating the next NASA scientist, playing on ever-bigger stages, or designing a successful fashion line—they will become worthy of the world’s attention and protection. “The world community got tired of our crying,” Sulaiman said. “But if we focus on our work and contribute to the countries where we live, one day they will come and ask what happened to us.”

Abduweli Ayup contributed reporting.

Source: FP