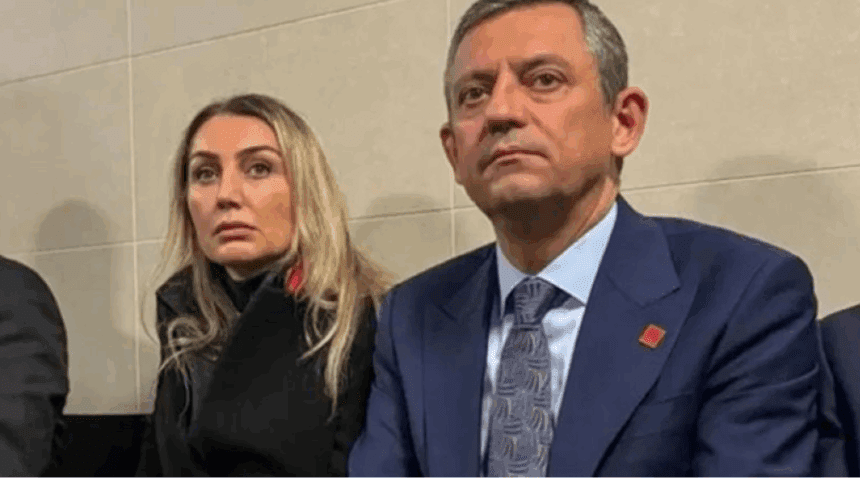

When Dilek Kaya İmamoğlu, the wife of jailed Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, told AFP that Western democracies’ silence had been “disappointing,” she echoed a line that has become central to the Republican People’s Party’s (CHP) international messaging: Europe claims to champion democracy, yet keeps quiet as Turkey’s opposition is targeted.

CHP leader Özgür Özel has made the same argument even more directly—aiming it not only at governments, but at Europe’s ruling social democratic and socialist parties, whom he says have been hesitant to stand with their Turkish “sister party” despite what he describes as an escalating crackdown.

But the renewed appeals to European solidarity have also reopened a politically sensitive file: the CHP’s documented participation, in the years after the July 15, 2016 coup attempt, in state-sanctioned delegations sent abroad to explain—and in practice help legitimize—Ankara’s narrative at a moment when the post-coup purge and allegations of torture and mass violations were already drawing global scrutiny.

Dilek İmamoğlu’s message: “Public conscience cannot be silenced”

In her AFP interview, Dilek İmamoğlu described the detention as deeply painful for her family, saying they “hold onto one another” and keep fighting. She said her husband’s message—“never lose hope”—has kept them standing. “The public conscience cannot be silenced,” she said, adding that hardship has pushed her toward solidarity rather than despair and that she trusts the will and conscience of the people.

She also voiced concern that Turkey is entering a dangerous legal and political terrain, arguing that decisions of the European Court of Human Rights and Turkey’s Constitutional Court are being ignored, the constitution is not being implemented, and “lawlessness” is being normalized. She expressed solidarity with the families of Selahattin Demirtaş and Osman Kavala—two emblematic cases often cited in debates over judicial independence.

The core political point, however, was aimed outward: Europe’s silence, she said, had been disappointing—though she stressed that the decisive support comes from millions inside Turkey who believe in justice, freedom, and democracy.

Özgür Özel’s Brussels complaint: the “sister parties” dilemma

Özel has amplified this line on the European stage. At a Party of European Socialists (PES) gathering in Brussels on December 17, he criticized what he portrayed as the reluctance of sister parties’ leaders in government to show visible solidarity as the CHP faces pressure at home.

His message was blunt: European social democrats cannot credibly oppose some authoritarians while maintaining pragmatic ties with others—especially, he argued, if they allow a sister party that claims to be positioned to win the next election to be isolated and crushed. Özel framed the issue as a choice Europe must make: a democratic Turkey next door with social democrats in power, or an entrenched authoritarianism sustained by “stable relations.”

The contradiction: CHP’s own role in selling Ankara’s post-coup line abroad

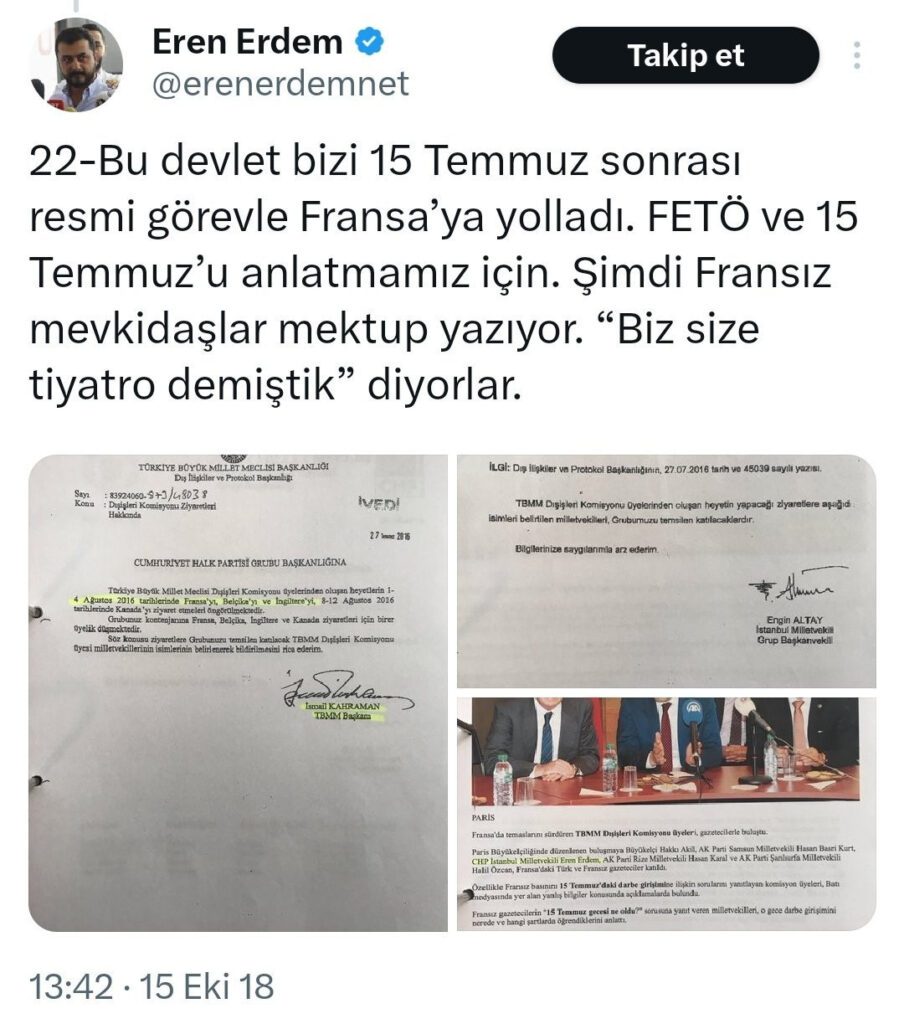

Yet critics say the CHP’s current reproach of Europe rests on a selective memory. In 2018, then-CHP lawmaker Eren Erdem publicly shared official documents and stated that CHP delegations were sent abroad on official assignments in the aftermath of July 15. According to Erdem’s account, the delegations’ mission was to promote the government’s framing of the coup attempt and to defend the state’s response to foreign audiences.

Erdem’s posts suggested that these efforts went beyond simply condemning a coup attempt in principle: they included assurances presented to foreign counterparts that there was no torture or mistreatment following the coup attempt—claims that conflict with the extensive public record of mass arrests, purges, and allegations of abuse reported by multiple rights monitors and media investigations over time.

In one of the most striking details in Erdem’s account, he said that French counterparts wrote back with a blunt remark—“We told you it was theatre”—a line frequently cited by critics as evidence that European officials privately doubted Ankara’s story even as formal diplomacy remained cautious.

Özel confirms the outreach—while reframing it

The issue has resurfaced again because Özel himself has acknowledged the broader fact pattern: that CHP deputies were involved in explaining Turkey’s July 15 narrative abroad. In Brussels, Özel recalled that President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan contacted the CHP on the night of July 15 and urged the party—because of its international connections—to help communicate Turkey’s position to the world as a coup attempt against democracy.

Özel’s intended framing is that Erdoğan later betrayed that unity—transforming from an alleged victim to an oppressor now using state power against rivals like Ekrem İmamoğlu. But critics argue that the admission unintentionally strengthens a different conclusion: Europe’s later caution and silence did not emerge in a vacuum; it was shaped in part by the early international messaging that the Turkish state exported—with opposition participation or acquiescence—at the moment the new post-coup order was being built.

“Why were you silent?”—after asking Europe to believe the state

This is where the political clash becomes sharper. Özel’s question to European socialists—why they are silent now—collides with the historical record that, after July 15, parts of the opposition were mobilized to help convince Europe that Ankara’s version of events was credible and that the state’s response was legitimate.

In other words, critics say, the CHP is now asking Europe to intervene morally and politically after years in which Europe was asked—sometimes explicitly—to treat the post-coup story as settled and to accept assurances that abuses were not systematic. If that is accurate, then Europe’s silence is not simply cowardice or hypocrisy; it may also reflect how effectively the “state narrative” was normalized internationally in the first place.

A political reckoning the opposition cannot avoid

None of this negates Dilek İmamoğlu’s personal anguish, or the very real political stakes of her husband’s detention. But it does raise a hard question for the CHP’s international strategy: can the party credibly demand principled solidarity from Europe without openly addressing its own role—whether by calculation, caution, or misjudgment—in legitimizing the post-2016 environment that made today’s repression possible?

As Turkey enters another phase of political escalation, the opposition’s problem may not only be how to challenge Erdoğan’s power, but how to confront a legacy in which lines between resistance and cooperation were, at critical moments, blurred. Without that reckoning, critics argue, calls for Western solidarity risk sounding less like a principled defense of democracy—and more like an appeal made after the machinery they once helped validate has turned against them.