Turkey’s foreign minister, Hakan Fidan, recently said in New York that export licenses from the U.S. Congress for General Electric F110 engines are “stalled,” adding that KAAN fighter production cannot begin without those approvals and describing the issue as a “systemic” constraint in the U.S.–Turkey defense channel.

His blunt line—that KAAN’s early production cannot begin without U.S. congressional licenses for GE F110 engines—landed with a thud in Ankara’s political echo chamber. The foreign minister didn’t discover CAATSA last week; he chose to put dependence on the record now, saying the licenses are “stalled” in Congress and must move for production to begin.

Turkey’s defense-procurement leadership responded by emphasizing program continuity. Presidency of Defense Industries (SSB) chief Haluk Görgün told state media that KAAN’s future is “in no way dependent on the engine of a single country,” that work on the domestic TF-35000 engine is proceeding, and that prototype engines are already delivered; he added that the serial-production plan remains on track. These points were echoed across Turkish outlets summarizing his statements.

KAAN flew its maiden sortie on February 21, 2024; officials continue to talk about deliveries later this decade, with foreign engines up front and an indigenous powerplant phased in. Turkey and Indonesia signed a contract for 48 KAAN at IDEF 2025, widely reported by international and Turkish media.

In this regard, export credibility is also at stake. That deal elevates the significance of near-term engine licensing for both domestic schedules and a first foreign customer, even as longer-term plans call for a shift to indigenous propulsion.

Fidan chose to say the quiet part out loud—at a sensitive moment. The timing matters: Turkey’s succession talk has moved from whispers to open positioning. At News About Turkey (NAT), we’ve argued for months that two tracks now overlap: a dynastic path with Bilal Erdoğan—the heir Erdoğan prefers to succeed him—and a technocratic path in which Fidan markets himself as the competent steward of constraints.

It also arrived amid a security-and-compliance chill rolling through the defense ecosystem. In late August, prosecutors moved against ASSAN Group, ordering TMSF trusteeship over 10 subsidiaries and detaining the owner and general manager in an “espionage” probe. Company accounts also show Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan and top military officers visiting its stand at the IDEF 2025 fair in İstanbul in July.

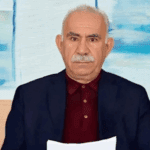

—-An Assan Group executive presents a model munition to Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan at the company’s IDEF 2025 stand in İstanbul. Photo: Assan Group.

That wasn’t the only tremor. Last week, Istanbul prosecutors announced arrests over commercial/military data leaks marketed via social platforms; Turkish mainstream outlets reported seven arrests and said ASELSAN-related product data and trade records were among the targeted material. Authorities described the case as ongoing.

Against this backdrop, the competitive map inside Turkey’s defense industry matters for how events are perceived. Baykar has become the country’s leading defense exporter by value and a global UAV brand, while TUSAŞ/TAI, ASELSAN and others anchor major air, electronics and missile programs. Public rankings and trade reporting show Baykar and TAI among the world’s top 50 aerospace companies by 2023 sales, and official data credited Baykar with topping Turkey’s defense-export list in 2024 amidst the sector’s overall growth, which resulted in record export totals last year. These facts help explain why procurement, licensing and enforcement decisions are often read through an industry-competition lens.

ASSAN operates in munitions and energetics rather than UAVs, so it is not a direct product competitor to Baykar; however, companies across different segments still compete for state attention, export channels, financing and skilled labor.

Against this tableau, the fairest reading is the simplest: Fidan turned a wonky procurement hurdle into a leadership trial. It also wouldn’t be surprising, in this climate, if President Erdoğan reassigns or sidelines Fidan in the near future. Erdoğan has repeatedly reshuffled cabinets and top posts to rebalance inner-circle dynamics and message discipline—elevating allies one year, rotating portfolios the next, and changing high-salience jobs with little warning. From the 2023 post-election reset to periodic ministerial swaps since 2021 and even this summer’s senior communications change, the pattern is established: mobility is a tool of control. If Fidan’s candor complicates the storyline, moving him to a “quieter” brief would fit that playbook—and would keep a pivotal insider inside the tent. None of this asserts any wrongdoing; it recognizes how personnel moves are used to manage influence and information in Turkey’s highly centralized system.

However, the senior insiders like Fidan are both architects and witnesses to the most controversial chapters of the last decade—before, during, and after July 2016—and therefore too valuable (or too risky) to leave unattended.

In short, Fidan’s New York sentence, in other words, wasn’t a gaffe. It was a résumé line.

By: News About Turkey (NAT)