A familiar warning has returned to headlines: Kurdish militants and political figures insist that Turkey’s renewed peace efforts “can collapse” unless Ankara meets core demands—especially around Abdullah Öcalan. The message is designed to create urgency and leverage. Yet for international observers, the more important question is not what the PKK and its affiliates say, but what they can realistically do.

The uncomfortable truth is that the PKK’s coercive rhetoric increasingly exceeds its operational capability inside Turkey. That gap matters because it distorts policy debate in Ankara, misleads outside audiences, and—most consequentially—undercuts Kurdish interests beyond Turkey, particularly in Syria.

The latest statements illustrate the pattern. In late November, a senior PKK executive told Agence France-Presse that the organization would take “no further actions” in the peace process and would wait for the Turkish state to move, setting out two demands: Öcalan’s freedom and constitutional recognition of Kurds in Turkey. In parallel, Salih Muslim, a senior figure in Syria’s Kurdish-led PYD, warned in an interview with bianet that Turkey should “keep its hands off” Syria if it wants the renewed peace efforts at home to succeed.

Even Abdullah Öcalan himself, speaking through DEM Party MP Gülistan Kılıç Koçyiğit after a prison-island visit last month, warned that Turkey’s renewed peace effort with the PKK “must succeed,” arguing that failure could trigger “coup mechanics”—meaning a return to crisis politics, emergency-rule dynamics, and broad crackdowns like those that followed the collapse of the 2013–2015 process.

On paper, these statements imply that the peace process is hostage to PKK-defined conditions—and that failure to comply will trigger meaningful escalation. But this framing no longer matches the battlefield reality that has taken shape over the last decade, and accelerated since 2019.

Turkey’s counterinsurgency environment has changed qualitatively. Persistent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; drone-enabled targeting; and a layered system of fortified outposts in strategic terrain have steadily reduced the PKK’s ability to move, mass, and sustain operations inside Turkey. In addition, Turkey has increased the frequency of drone strikes against the PKK in Syria and Iraq after 2019, using “low-cost, persistent airpower” to hit leaders and cadres in areas previously hard to reach. In southeastern Turkey, physical control measures—checkpoints and hardened security nodes—also expanded after the breakdown of the earlier peace period. Even the “kalekol” system (hardened outposts) highlights how Ankara’s strategy leaned on new permanent outposts designed to dominate terrain and narrow guerrilla freedom of maneuver.

The outcome is not the disappearance of PKK violence, but its transformation. The PKK can still conduct limited attacks and symbolic operations; it can still mobilize political messaging and attempt to set “terms.” What it struggles to do—at least inside Turkey—is sustain a strategic campaign that compels Ankara through force.

One way to see that asymmetry is in conflict-event data. ACLED reported that in 2024 the PKK carried out 218 remote attacks against Turkish forces—an increase compared with earlier years, but “marginal” relative to Turkey’s 4,593 attacks on PKK targets in the same year. Whatever one thinks of the political trajectory, this gap reflects a hard military fact: the PKK is under significantly greater kinetic pressure than it can impose. That is a weak foundation for credible “the process will collapse” leverage.

This is why the PKK’s warnings should not be treated as a decisive factor that forces Ankara’s hand. Peace initiatives can fail for many reasons—mistrust, domestic polarization, competing bureaucratic interests, spoilers, regional shocks. But if a renewed process breaks down, the likely security outcome is not a return to the 1990s or the mid-2010s urban conflict cycle; it is more likely a continuation of the current pattern: episodic PKK violence, heavy Turkish counter-strikes, and political hardening—without the PKK regaining a strategic fighting role in Turkey.

In that sense, the PKK is already drifting toward de facto history—if not already obsolete— as a strategic military actor against the Turkish state. The process—if it continues—will only accelerate that trajectory, turning the PKK’s armed campaign into a closed chapter and leaving politics, law, and identity questions to dominate the agenda. International readers should recognize what this means: Ankara has less reason to treat PKK statements as security determinative, and more reason to treat peace as a political choice—pursued (or not) according to domestic calculations.

But there is a second, more regional consequence that Kurdish actors themselves sometimes understate: PKK-style “conditional threats” are not cost-free for Kurds beyond Turkey, especially in Syria.

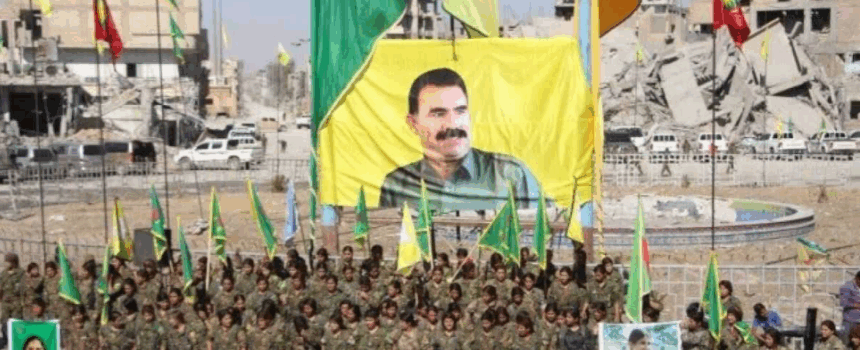

Salih Muslim’s argument—separate the tracks, don’t fuse Turkey’s domestic process with Syria—implicitly acknowledges that Syrian Kurds operate under a strategic vulnerability: Ankara’s conviction that the SDF is linked to the PKK. In that context, every time PKK or SDF figures project a message of coercion (“no more steps,” “without Öcalan, the process fails”), it reinforces the very linkage narrative Syrian Kurdish leaders say they want to avoid. It gives Ankara political ammunition to securitize Syria, to frame Kurdish self-administration as an extension of a Turkish internal threat, and to justify pressure on Damascus and on the integration or restructuring of Kurdish-led forces.

In plain terms: potential weak PKK attacks and loud PKK rhetoric do not merely “pressure Turkey.” They can damage Kurdish negotiating space in Syria by making Kurdish autonomy look, to Ankara and to many regional actors, like a security problem rather than a constitutional question.

This is precisely why PKK “collapse” warnings should not be over-weighted. Ankara’s incentives are not simply shaped by threats; they are shaped by the ability to narrate outcomes at home. If Ankara chooses to proceed, it can sell steps as victory. If it chooses to stall, it can blame militancy. Either way, the PKK’s ability to alter Turkey’s strategic calculus through force is far smaller than its spokespeople suggest.

Geography amplifies this vulnerability. Northern Iraq’s Kandil Mountains—where PKK headquarters have long been situated—are rugged and difficult terrain, historically well-suited for guerrilla concealment and depth. Northeast Syria, by contrast, is dominated by plains, steppe, and broad, open spaces in the Jazira/Upper Mesopotamian basin—terrain that is comparatively negotiable, easier to surveil, and far more accessible to conventional military movement. It is also very close to Turkey’s border—meaning that, if Ankara chooses escalation, the physical barriers to intervention are lower than in Kandil’s mountain geography.

This matters because northeast Syria is not just strategically exposed; it is strategically valuable. The region contains critical agricultural zones and key natural resources. The region between the Euphrates and Tigris produces oil, water, and wheat—three pillars of economic power in a divided Syria. In such an environment, control is contested not only by Damascus and local actors, but also by external stakeholders who view these assets as essential to Syria’s reconstruction and to regional leverage. For Ankara, a stable, manageable Kurdish-administered strip on its border should be preferable to chaos—but Ankara (not Erdogan) also has strong incentives to prevent any Kurdish entity it views as PKK-linked from consolidating sovereignty-like attributes.

SDF composition adds another layer. Despite the SDF’s Kurdish-led command structure, multiple analyses and official statements have described an Arab-heavy rank-and-file. This reality is often missed in international debate: northeast Syria’s governance and security equation is not only “Kurdish.” It is also tribal, Arab, local, and fragile. In such a setting, importing PKK-driven rhetoric—especially rhetoric that implies the Syria track is hostage to the Turkey track—can be destabilizing internally while handing Ankara a political pretext externally.

Finally, Erdogan’s domestic political calculus helps explain why PKK threats are less determinative than they appear. Erdoğan’s Turkey has repeatedly used “terror-free Turkey” language as a political instrument—mobilizing nationalist constituencies and framing any state action as a product of strength rather than compromise. In such a framework, Ankara can pursue a process while insisting it is not conceding, can delay hard decisions while claiming progress, and can repackage outcomes as victory.

At the same time, the regional reality may be nudging Turkey toward a pragmatic accommodation with Kurdish de facto autonomy in Syria—though likely in a controlled, deniable form. That does not necessarily mean formal recognition. It can mean something closer to an accepted reality under a new Syrian order: Kurdish-heavy municipalities, decentralized local governance, and security arrangements that curb PKK-linked structures while allowing a form of functional autonomy to persist. Whether one agrees with that trajectory or not, it highlights a key point: Ankara’s decisions will be shaped by state interests, regional constraints, and alliance management—not by PKK rhetorical posturing.

A durable peace—if it is to exist—will not be won by rhetorical brinkmanship from a militarily diminished movement. It will be built by political and legal engineering: representation, rights, reintegration mechanisms, and credible guarantees. And for Kurds outside Turkey, especially in Syria, the priority should be reducing linkages that invite securitization—not reinforcing them through threats that no longer match capability.

In summary, Ankara should not interpret the warnings about the PKK’s “collapse” as a bargaining chip, as these warnings no longer accurately represent the current balance of power. Additionally, Syrian Kurds, who are operating in much more fragile conditions, should avoid adopting that rhetoric in a situation where the geography is less forgiving, resources attract competing interests, and the West—especially the U.S., which has pushed both sides to pursue a renewed peace process—remains a critical factor in determining what level of autonomy can realistically endure.

By: News About Turkey (NAT)