This article is part of our special report ‘Belt and Road’: Linking up Europe and Asia.

Despite sharing growing strategic interests with Russia and China, Ankara remains economically much more closely integrated with the West, if not even dependent, writes Nicola P. Contessi.

Dr. Nicola P. Contessi, is an Academic Council Member at the European Neighbourhood Council (ENC) and specialises in Silk Road politics, global governance, international transportation, and security policy. @ENC_Europe

Turkey’s attitude toward the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) has raised much speculation ever since it obtained the status of Dialogue Partner in 2012. Conjectures intensified when then Prime Minister Erdoğan requested an upgraded status within the SCO just one year later. Was Ankara drifting away from the Euro-Atlantic fold? Was it living up to the “multi-dimensional and multi-track foreign policy” it had declared 10 years earlier? Or was it merely a provocation, intended to improve its bargaining leverage in the lingering negotiations on EU membership?

The answer to these questions has been as elusive as Turkey’s ambiguity. Statements from Ankara oscillate between the pursuit of observer status and full membership, but president Erdoğan’s latest remarks in November 2016 were perceived quite widely as if Turkey was seeking full membership. Nonetheless, what appears to be at stake remains the observer status. Yet, in December 2017 Xinhua quoted a Turkish diplomat stating his country has a pending full membership bid.

Whereas Turkey’s geopolitical and geo-cultural references have been swinging steadily eastwards in the last decade, entrenched historical and political realities appear to inhibit a deeper involvement with SCO.

Despite sharing growing strategic interests with Russia and China, Ankara remains economically much more closely integrated with the West, if not even dependent. In particular, Europe provides 75% of foreign direct investment and 56% of loans. Moreover, notwithstanding non-trivial and growing economic activity within its space, the SCO offers neither a free trade area nor a common market.

In the security sphere, Turkey is closely integrated with the Euro-Atlantic community through binding institutional arrangements such as NATO. These ties, which Ankara is unlikely to break, are probably destined to disappoint any aspiration of engaging the SCO without making a clear choice as a deeper involvement in that organization would hardly be compatible with its NATO obligations.

On the other hand, whether the current membership would be comfortable granting Turkey such recognition remains to be seen, and the SCO framework is flexible enough as to allow fairly substantial participation even at more junior levels of involvement. For instance, its status as a simple Dialogue Partner did not preclude Turkey from attaining the chairmanship of the SCO Energy Club for 2017.

Turkey’s 2016 upgrade request was denied. While, in the name of Turkic solidarity the Central Asian “caucus” might not object in theory, China and / or Russia may hesitate. Sure enough, Moscow, possibly backed by Iran, already an SCO Observer, differed with Ankara over Syria.

However, Turkish commentators at the time appeared to be suspecting China. Even though Ankara dubs the Uyghur people as “the friendly bridge between Turkey and China”, the Uyghur question remains a major irritant. Chinese authorities regularly accuse Turkey of allowing terrorists a safe passage into China. Erdoğan himself once referred to the July 2009 Chinese suppression of a rebellion in Urumqi as “savagery” and even “genocide”. Turkey, which at the time was a non-permanent member, tried to bring the matter to the UN Security Council angering Beijingprofoundly. Then of course, there is the strong persuasion in the Zhongnanhai that Ankara is only trying to raise its price with its Western allies.

Much water has passed under the bridge since that first refusal, and after almost breaking off all ties Moscow now sees an opportunity in post–coup-attempt Turkey. According to some, is not opposed to the possibility of even granting it full membership. For Russia, Turkey means business: a major trading partner, the perfect client for its natural gas and a prospective transit route for onward gas exports. Nonetheless, the Russian military seems more sceptical: one retired colonel sentenced that without leaving NATO, Turkey could not join the SCO.

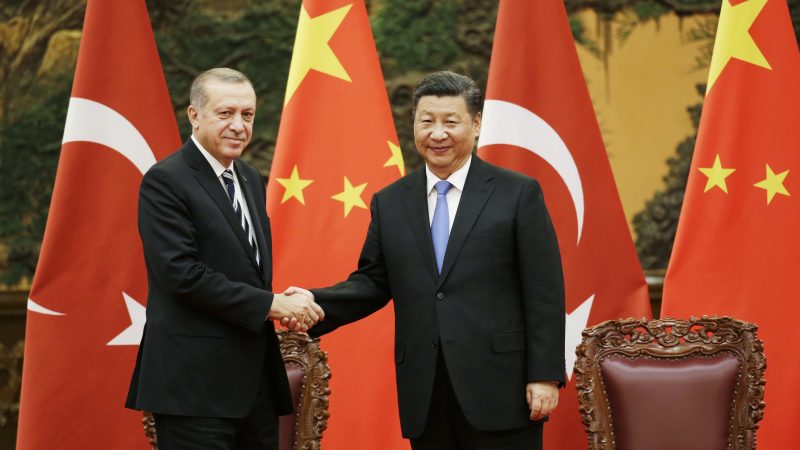

At any rate, Erdoğan second plea received a lukewarm response from China’s Foreign Ministry stating that Turkey was “already a dialogue partner” and that Beijing “attaches importance to Turkey’s aspiration to further deepen cooperation with the SCO”. The Uyghur issue again lurked in the background as only one year earlier and just weeks before Erdoğan’s 2015 official visit to China, Istanbul saw a series of anti-Chinese protests.

In sum, it is hard to predict whether Turkey may eventually obtain what Erdoğan claims it wants, though it’s already arduous to gauge what exactly he wants. While the issue appears to have receded from his priorities, the matter remains rather inscrutable. Both China and Russia are allergic to pan-Turkism –though China probably more so today than Russia– and both may question Erdoğan’s trustworthiness and the durability of Turkey’s political commitments in the future. Notwithstanding their numerous overtures, Beijing and Moscow may still regard Turkey as a potential “Trojan horse of the West”. Even though Turkey has intensified official visits and other contacts with both capitals since 2016, they are likely to demand more substantial proof of loyalty from Erdoğan.

By Dr. Nicola P. Contessi

Source: Protothema